Michael Harrop

Well-known member

I posted about this a few years ago elsewhere [1][2][3] and I'm copying all the info here for easy discussion.

"While fecal microbiota is partially normalized by extended co-housing, mucosal communities associated with the proximal colon and terminal ileum remain stable and distinct". Comparison of Co-housing and Littermate Methods for Microbiota Standardization in Mouse Models (May 2019). https://www.cell.com/cell-reports/fulltext/S2211-1247(19)30488-7

For the people who don't know, mice eat each other's poop, thus naturally do FMT when co-housed.

This study seems to show that FMT is not enough to change the mucosal microbiome. Thus it seems like something like this would be necessary to enhance FMT:

Previously I emailed a bunch of IBS & CFS researchers asking them to test that mucosal clearing either by itself or in conjunction with FMT, but it didn't seem like any were willing/able.

Someone should also test (in vitro then in mouse models) various substances that degrade/clear the gut mucosa to see if you can find one that safely boosts the ability of FMT to replace the mucus microbiota. Basically a chemical version of the method above. N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) might be one. Try while liquid fasting too.

Someone suggested:

And relevant to the "in vitro" part: GuMI: New In Vitro Platforms to Parse the Human Gut Epithelial-Microbiome-Immune Axis https://grantome.com/grant/NIH/R01-EB021908-02

My worry is that the fecal microbiome isn't adequate, and a gut microbiome transfer will require harvesting the mucosal microbiome. But an experiment like this should help to further our understanding of this.

I'm thinking there might be some type of layers. Like the microbes transferred by FMT are only able to occupy some top layer or small niches where they're able to feed on the food coming through, but unable to penetrate further down into the mucus.

This is very much inline with my own current FMT experience where the donor microbes seem to be very easily lost - such as by using iodized salt (iodine is an antimicrobial) - and I have to keep adding them.

It should be possible to do a mucosal microbiota transplant by swabbing/collecting mucosa samples from the colon, immediately submerging them in saline to protect anaerobes, and then feeding that liquid to other mice and see how it compares to FMT/co-housing. I would also compare feeding the mucosa liquid while the recipient mouse was fasting vs not fasting.

I did a google scholar search for "mucus microbiota transplant" and didn't see anything on it.

We could even do it in humans, it would just be slightly more invasive for the donor than FMT. I've had a colonoscopy done while I was not sedated. It was painful as the object made its way through the turns especially, but perhaps we don't need to use such a large object, making it less painful.

For reference, the mucosal microbiota seems to be significantly different from the fecal microbiota:

Conflicting data:

Maybe the ultimate end game will be clearing the mucosa in the recipient and using mucosa microbiota from the donor, but for now, maybe whichever one is easier could be a significant improvement on its own compared to standard FMT.

UPDATE:

"While fecal microbiota is partially normalized by extended co-housing, mucosal communities associated with the proximal colon and terminal ileum remain stable and distinct". Comparison of Co-housing and Littermate Methods for Microbiota Standardization in Mouse Models (May 2019). https://www.cell.com/cell-reports/fulltext/S2211-1247(19)30488-7

For the people who don't know, mice eat each other's poop, thus naturally do FMT when co-housed.

This study seems to show that FMT is not enough to change the mucosal microbiome. Thus it seems like something like this would be necessary to enhance FMT:

By destroying the mucous membrane in the small intestine and causing a new one to develop, scientists stabilized the blood sugar levels of people with type 2 diabetes. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/oct/24/spectacular-diabetes-treatment-could-end-daily-insulin-injections

Duodenal Mucosal Resurfacing Elicits Improvement in Glycemic and Hepatic Parameters in Type 2 Diabetes—One-Year Multicenter Study Results (2018): https://diabetesjournals.org/diabetes/article/67/Supplement_1/1137-P/54118/Duodenal-Mucosal-Resurfacing-Elicits-Improvement

When destroying the membrane you're basically clearing the forest, which includes pathogens which may be responsible for diabetes. It's likely that if their method actually clears and replaces it without significant damage (unlike antibiotics) it could help many more conditions than diabetes.

Previously I emailed a bunch of IBS & CFS researchers asking them to test that mucosal clearing either by itself or in conjunction with FMT, but it didn't seem like any were willing/able.

Someone should also test (in vitro then in mouse models) various substances that degrade/clear the gut mucosa to see if you can find one that safely boosts the ability of FMT to replace the mucus microbiota. Basically a chemical version of the method above. N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) might be one. Try while liquid fasting too.

Someone suggested:

Utilizing proteolytic enzymes may be interesting. Even to go as far as doing a retention enema to allow the enzymes to break down biofilms and the mucosal layers.

And relevant to the "in vitro" part: GuMI: New In Vitro Platforms to Parse the Human Gut Epithelial-Microbiome-Immune Axis https://grantome.com/grant/NIH/R01-EB021908-02

My worry is that the fecal microbiome isn't adequate, and a gut microbiome transfer will require harvesting the mucosal microbiome. But an experiment like this should help to further our understanding of this.

I'm thinking there might be some type of layers. Like the microbes transferred by FMT are only able to occupy some top layer or small niches where they're able to feed on the food coming through, but unable to penetrate further down into the mucus.

This is very much inline with my own current FMT experience where the donor microbes seem to be very easily lost - such as by using iodized salt (iodine is an antimicrobial) - and I have to keep adding them.

Mucosal microbiota transplant?

I was thinking more about "while fecal microbiota is partially normalized by extended co-housing, mucosal communities associated with the proximal colon and terminal ileum remain stable and distinct".It should be possible to do a mucosal microbiota transplant by swabbing/collecting mucosa samples from the colon, immediately submerging them in saline to protect anaerobes, and then feeding that liquid to other mice and see how it compares to FMT/co-housing. I would also compare feeding the mucosa liquid while the recipient mouse was fasting vs not fasting.

I did a google scholar search for "mucus microbiota transplant" and didn't see anything on it.

We could even do it in humans, it would just be slightly more invasive for the donor than FMT. I've had a colonoscopy done while I was not sedated. It was painful as the object made its way through the turns especially, but perhaps we don't need to use such a large object, making it less painful.

For reference, the mucosal microbiota seems to be significantly different from the fecal microbiota:

Mucus: A Special Home of Our Microbes (2018): https://www.karger.com/Article/FullText/495115#scrollNav-4 "So far, we know that the mucus of surface epithelia seems to be one of the most important habitats for host-associated bacteria"

Differential clustering of fecal and mucosa-associated microbiota in ‘healthy’ individuals (2018): https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1751-2980.12688 "Analysis of faecal samples that have been transported at ambient temperature does not adequately reflect the colonic mucosa-associated microbiota in healthy individuals"

Gut mucosal-associated microbiota better discloses Inflammatory Bowel Disease differential patterns than faecal microbiota (2018): https://www.dldjournalonline.com/article/S1590-8658(18)31260-X/abstract

Bacteriophage Adherence to Mucus Mediates Preventive Protection against Pathogenic Bacteria (Mar 2019): https://journals.asm.org/doi/10.1128/mbio.01984-19

Analysis of Transcriptionally Active Bacteria Throughout the Gastrointestinal Tract of Healthy Individuals (June 2019) https://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085(19)40986-4/fulltext "In an analysis of saliva, mucosal, and fecal samples from 21 healthy adults, we found each individual, and each GI region, to have a different bacterial community. The fecal microbiome is not representative of the mucosal microbiome."

Composition of the mucosa-associated microbiota along the entire gastrointestinal tract of human individuals (May 2019) https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2050640619852255 "gastrointestinal location is a larger determinant of mucosal microbial diversity than inter-person differences. The bacterial load of mucosal samples decreased from oesophagus to proximal ileum, but drastically increased again in the lower GI tract. The composition of the microbiota markedly changes along the GI tract with larger diversity in the lower GI tract than the upper GI tract."

Comparative microbiome analysis of paired mucosal and fecal samples in Korean colorectal cancer patients (Jun 2025, n=30) https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/oncology/articles/10.3389/fonc.2025.1578861/full - PEG bowel preparation.

Conflicting data:

Maybe the ultimate end game will be clearing the mucosa in the recipient and using mucosa microbiota from the donor, but for now, maybe whichever one is easier could be a significant improvement on its own compared to standard FMT.

UPDATE:

This is a literature review I did evaluating the above-cited evidence that there is a significant difference between the mucosal and fecal microbiomes in humans.

My conclusion is that there is insufficent evidence due to two issues with the research:

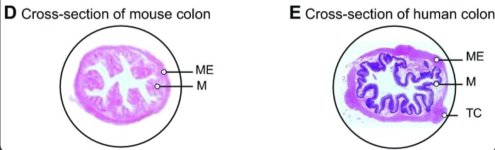

1) the use of mouse studies

2) the use of bowel prep prior to endoscopic collection of mucosal samples in humans.

The GI tracts of mice are different from that of humans on a structural and cellular level so we should be careful when attempting to translate scientific conclusions from one to the other that may be affected by these differences. More info at the end of the post. Osmotic laxative bowel prep prior to colonoscopy entails consuming large amounts of laxatives that flood the mucosa with water and clear out huge amounts of bacteria. Expecting the mucosal microbiota to look similar before and after this type of prep is a poor assumption that should have been cited as a limitation in these studies.

Last edited: